Industrial Revolution Time Period: When and Why

Table of Contents

industrial revolution time period

“When Did the World Start Clanking?”: Pinning Down the industrial revolution time period Without Losing Our Marbles

Right—picture this: you’re sipping a cuppa in a Derbyshire village, 1760. The only sounds? A blacksmith’s hammer, a distant cow, and your own thoughts. Fast-forward thirty years: same village, now vibrating to the *clank-hiss-whirr* of Arkwright’s water frame, the *rumble* of coal carts, and the *shout* of a foreman clocking you in. So—when *exactly* did the industrial revolution time period kick off? Not with a bang, nor a royal decree—but with a slow, sooty *creak* of inevitability. There’s no neat start-date stamped on a gearbox (though historians love arguing over it like it’s the last sausage at a BBQ). Most agree the industrial revolution time period simmered from the 1760s, boiled over in the 1780s, and kept bubbling—sometimes violently—well into the mid-19th century. And no, it didn’t “end” so much as *evolve*, like a steam engine upgraded to electricity, then code. The industrial revolution time period isn’t a chapter—it’s the whole bloody book, with footnotes in grease and tears.

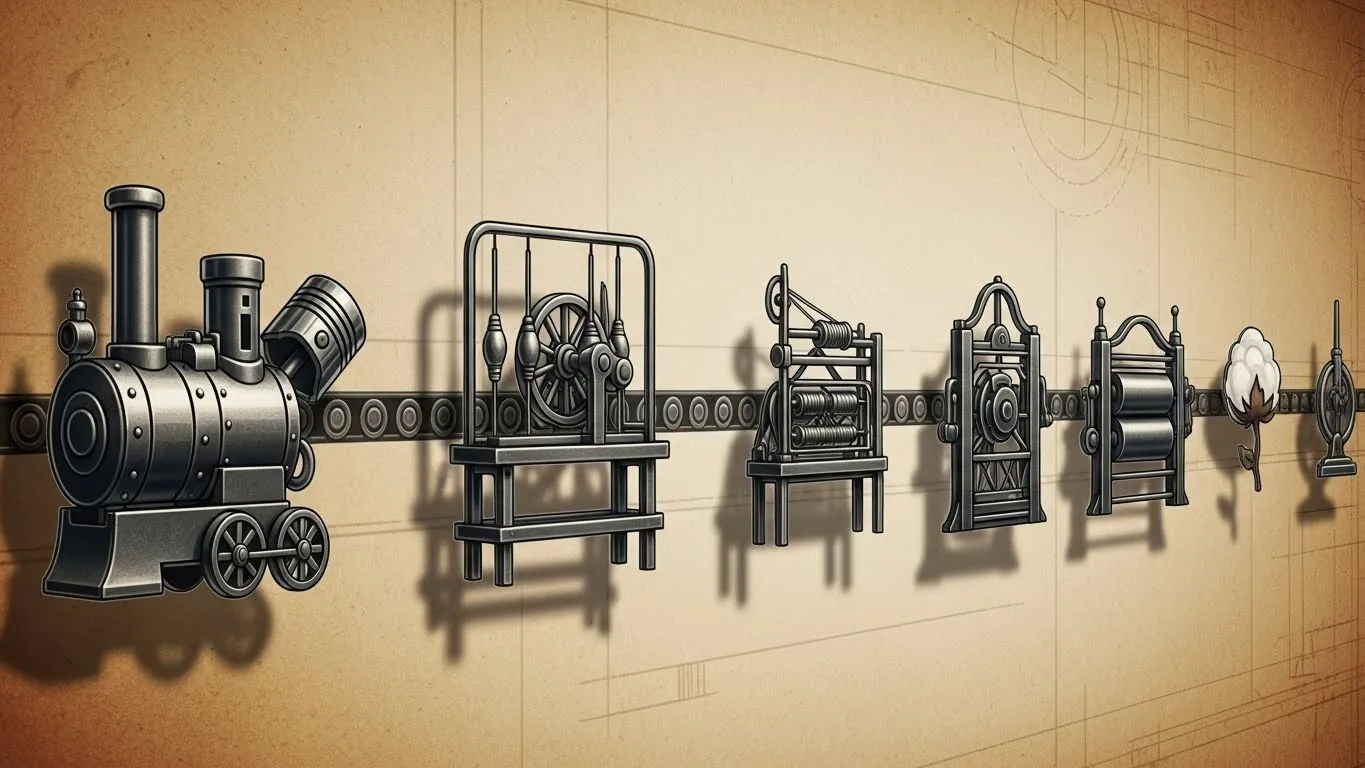

The “First Wave”: Cotton, Coal, and the Quiet Earthquake (c. 1760–1840)

Ah, the OG era—the one with waistcoats, waterwheels, and child labour laws that were… *suggestions*. The industrial revolution time period truly found its rhythm in textile mills and iron forges. Richard Arkwright’s water frame (1769) didn’t just spin cotton—it spun *social structure*. Suddenly, work wasn’t “when the sun’s up”; it was “when the bell rings”. And coal? Went from “fuel for hearths” to “the black blood of progress”. By 1800, Britain produced *10 million tonnes* of coal a year—*triple* what it did in 1750. Steam engines (thanks, James Watt, 1776) weren’t yet powering trains—but they *were* pumping mines, blowing bellows, and grinding grain. This phase of the industrial revolution time period was rural-to-urban *en masse*: Manchester’s population leapt from 17,000 (1760) to 300,000 (1850). That’s not growth—that’s *invasion*.

Why Britain? Luck, Lumps of Coal, and a Dash of Legal Looseness

Let’s be frank: the industrial revolution time period didn’t land in Britain by accident. Three things lined up like planets in a dodgy pub astrology chart: 1. Resources—coal *and* iron ore, often side-by-side (looking at you, Midlands). 2. Capital—profits from trade, slavery, and enclosure acts meant someone had brass to risk. 3. Institutions—patent law (Watt’s engine was protected!), stable-ish government, and—crucially—*no guilds* strangling innovation. Compare that to, say, France: brilliant minds, yes—but rigid craft monopolies and revolution-induced chaos delayed their industrial revolution time period by decades. As economic historian Joel Mokyr quipped: “Britain had the right mix of *greed*, *genius*, and *geology*.” And maybe just a pinch of stubbornness—the sort that says, “Aye, let’s try bolting a kettle to a cart and see what happens.”

The Human Clock: How Factory Whistles Replaced Church Bells

Before the industrial revolution time period, time was *organic*: plant by the moon, harvest by the sun, rest when the cows came in. Factories changed all that. Suddenly, “noon” wasn’t when the shadow hit the door—it was when the foreman’s pocket watch said so. Punch clocks (1888, Willard Bundy) turned minutes into *currency*. A 14-hour shift wasn’t “tiring”—it was *14 units of labour sold*. One 1833 Factory Commission report noted children working “from 6 a.m. to 9 p.m., with 40 minutes for meals”—and *that* was considered “improved conditions”. The industrial revolution time period didn’t just mechanise looms—it mechanised *lives*. Even leisure got scheduled: music halls opened at 7:30 *sharp*. Punctuality became moral virtue. As one factory poster (c. 1840) warned: “Five Minutes Late is Theft of Company Time.” Grim. But effective.

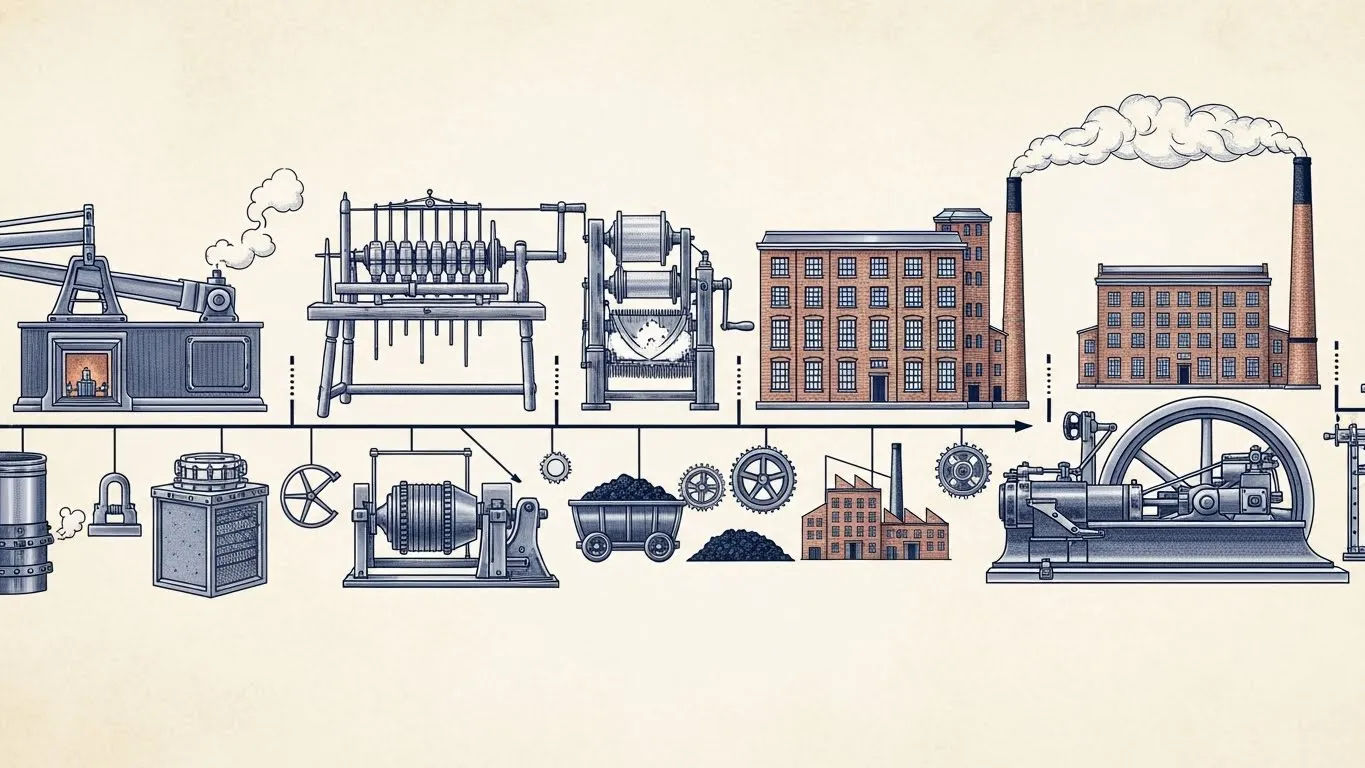

The Second Surge: Steel, Steam, and the Shrinking Globe (c. 1840–1900)

If the first wave was cotton and clatter, the second was *steel and scale*. The industrial revolution time period matured—got louder, faster, and frankly, a bit show-offy. Bessemer’s converter (1856) turned iron into steel *en masse*; railways exploded (UK track mileage: 1,500 mi in 1840 → 18,000 mi by 1890); and steamships shrank oceans. By 1870, you could ship wheat from Chicago to Liverpool for *1d per bushel*—a tenth of 1820s cost. Telegraph wires hummed news across continents in *minutes*, not months. This phase of the industrial revolution time period birthed *corporations*, *stock exchanges*, and *advertising* (“Buy Bovril—it’s *scientific*!”). It’s also when folks started calling it “the Industrial *Revolution*”—as if realising, belatedly, they’d lived through an earthquake while arguing about tea.

The “Third” and “Fourth” Waves—Or: When Your Granddad’s Revolution Got a Software Update

Hold up—didn’t we say the industrial revolution time period ended in 1840? Ah, semantics. Modern scholars *love* slicing the pie: First Industrial Revolution: Steam, mechanisation (1760–1840) Second: Electricity, mass production (1870–1914) Third: Digital, computers (1960s–2000s) Fourth: AI, IoT, automation (2010s–?) But—let’s not kid ourselves. The *core* industrial revolution time period—the one that turned agrarian societies upside-down—was *British*, *steam-powered*, and *19th-century*. The rest? Evolutions. As historian Eric Hobsbawm warned: “Calling the internet age an ‘Industrial Revolution’ is like calling a smartphone a ‘horse’ because it moves you forward.” Fair point. The original industrial revolution time period wasn’t about speed of data—it was about *speed of change in human existence*.

Regional Ripples: When the North Pulled Ahead of the South (and Wales Got Coal-Rich & Rainy)

The industrial revolution time period didn’t blanket Britain evenly—it *streaked* it. The Northwest (Lancashire, Yorkshire) became textile central: mills, chimneys, and rows of back-to-backs. The Midlands (Birmingham, “Workshop of the World”) forged everything from pen nibs to pistols. South Wales? Coal and steel—*so much* coal that Cardiff became the world’s busiest port by 1913. Meanwhile, much of the South and East remained agricultural—beautiful, yes, but economically… sleepy. This divide *still* echoes. A 2022 ONS report showed median weekly earnings in London: £821; in parts of South Wales: £498. That’s not coincidence—that’s the industrial revolution time period legacy, fossilised in wage packets and rail subsidies. Some regions rode the wave. Others got washed over.

Women, Children, and the Unseen Shifts in the industrial revolution time period

Textbooks show men at looms—but half the early mill workforce was *female*. And in mines? Children as young as five crawled through tunnels too low for adults, dragging coal sleds on all fours. A parliamentary report (1842) recorded a girl “harnessed like a beast”, hauling half a tonne “by a chain passing round her waist and between her legs”. Horrific—but economically *rational* at the time. The industrial revolution time period didn’t just change *what* work was done—it redefined *who* did it, and *how they were valued*. Factory Acts (1833, 1844, 1847) slowly curbed the worst excesses—but “protection” often meant *pushing women into lower-paid domestic roles*. Progress, yes—but uneven, and often cruel. The industrial revolution time period gave us unions, yes—but only after decades of bodies broken to prove the need.

Cultural Feedback Loop: How Novels, Paintings, and Pub Songs Made Sense of the industrial revolution time period

People didn’t just *live* the industrial revolution time period—they *processed* it. Dickens didn’t invent poverty—but *Hard Times* (1854) made Coketown’s “serpents of smoke” *felt*. Turner’s *Rain, Steam and Speed* (1844) didn’t just show a train—it captured *anxiety*: nature vs machine, past vs future. Even folk songs shifted: “The Collier’s Rant” (pre-1760) mourned pit dangers; by 1830, “The Hand-Loom Weaver’s Lament” howled: “You lads of the factory, so merry and gay,

Come pity the hand-loom weaver, now driven away!” Art wasn’t decoration—it was documentation. The industrial revolution time period was so disorienting, society *had* to make meaning. Poetry, protest, painting—all were coping mechanisms. As Wordsworth fretted in 1807: “Little we see in Nature that is ours.” The industrial revolution time period didn’t just change landscapes—it changed *longing*.

Where to Wander Next: Archives, Attics, and Alternate Timelines

If this glimpse into the gears and grime has left you wanting more (and let’s be honest—you’re now mentally redesigning your kitchen with Victorian rivets), here’s where to amble further. Pop over to the homepage of The Great War Archive, lose yourself among the stacks in History, or dive into the nuanced tangle of Postcolonial and Post-Colonial: Key Differences—because, of course, Britain’s industrial boom didn’t happen in a vacuum. Global resources, coerced labour, imperial markets? All part of the engine. But that’s a kettle for another day. For now—keep questioning *when*, *why*, and *who paid the price*.

FAQ: Navigating the industrial revolution time period Without a Pocket Watch

What are the 4 periods of the Industrial Revolution?

Ah, the “four revolutions” model—it’s a handy framework, but take it with a pinch of soot. Scholars break it thus: First (c. 1760–1840): Steam, water power, mechanised textiles (UK-centric). Second (c. 1870–1914): Steel, electricity, railways, mass production (US/Germany rise). Third (c. 1960s–2000s): Digital tech, computers, automation. Fourth (c. 2010s–present): AI, IoT, big data, cyber-physical systems. Crucially, the *original* industrial revolution time period refers to the first—British, steam-driven, society-shattering. The rest are sequels. Not all historians agree on the numbering—but they *do* agree: phase one changed everything.

When did the Industrial Revolution begin and end?

No tidy bookends here—the industrial revolution time period began *gradually* in Britain around the 1760s (Arkwright’s water frame, 1769; Watt’s rotary engine, 1781), accelerated through the 1790s–1830s, and—depending on who you ask—“ended” somewhere between 1830 and 1850, when railways, factories, and urban life became *normal*, not novel. But really, it didn’t “end”—it *diffused*. Belgium adopted it by 1830, the US by 1850, Germany by 1870. So while the *core British phase* fits roughly 1760–1840, the global industrial revolution time period stretched well into the 20th century. Think of it like ink in water: the drop hits at 1760, but the swirl keeps going.

What is the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Industrial Revolution?

Simplified: 1st: Steam & textiles (1760–1840) – “Let’s power looms with boiling water.” 2nd: Steel & electricity (1870–1914) – “Let’s mass-produce cars *and* light entire cities.” 3rd: Digital & automation (1960s–2000s) – “Let’s replace levers with logic gates.” Each built on the last, but the *1st* is the true industrial revolution time period—the one that severed humanity from agrarian rhythms. Interestingly, the 2nd Industrial Revolution saw *faster* GDP growth than the first (UK: 1.2% p.a. 1870–1913 vs 0.9% 1801–1831). So the *real* acceleration? Came later. But the *shock*? That was all 1760–1840.

When was the UK Industrial Revolution?

The industrial revolution time period in the UK ran roughly from the **1760s to the 1840s**, with the *most intense transformation* between **1780 and 1830**. Key milestones: • 1769: Arkwright’s water-powered mill (Cromford) • 1776: Watt’s improved steam engine patented • 1825: First public railway (Stockton–Darlington) • 1833: First effective Factory Act (limited child labour) By 1851, over 50% of Britons lived in towns—up from 20% in 1750. That demographic flip—the *urban majority*—is the clearest marker that the industrial revolution time period had succeeded. Britain was no longer a nation of villages. It was a nation of *shifts*.

References

- https://www.britannica.com/event/Industrial-Revolution

- https://www.history.ac.uk/article/industrial-revolution-was-it-inevitable

- https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/industrial-revolution/

- https://eh.net/encyclopedia/the-industrial-revolution-in-world-history/