1st Computer Ever Revolutionary Machine

- 1.

“Wait—was the *first* computer built out of wood and prayers?!” Unpacking the Myth, the Machine, and the Mad Genius Behind It

- 2.

‘Computer’ Used to Be a Job Title (and It Paid 30 Shillings a Week)

- 3.

Colossus: The Secret War Hero That Couldn’t Be Mentioned Until 1975

- 4.

ENIAC: The Glamorous American Cousin Who Got All the Headlines

- 5.

Pre-Electronic Contenders: From Babbage’s Dream to Turing’s Blueprint

- 6.

“But What About…?”—Zuse, Atanasoff, and the Transatlantic Patent Wars

- 7.

Timeline Tangle: A Rough Guide for the Chronologically Bewildered

- 8.

“Did Computers Exist in 1940?”—Spoiler: *Kind Of*, If You’re Generous

- 9.

From Valves to Virality: Why the ‘First’ Still Matters in 2025

- 10.

Where the Past Meets the Present—And Why You Should Care

Table of Contents

1st computer ever

“Wait—was the *first* computer built out of wood and prayers?!” Unpacking the Myth, the Machine, and the Mad Genius Behind It

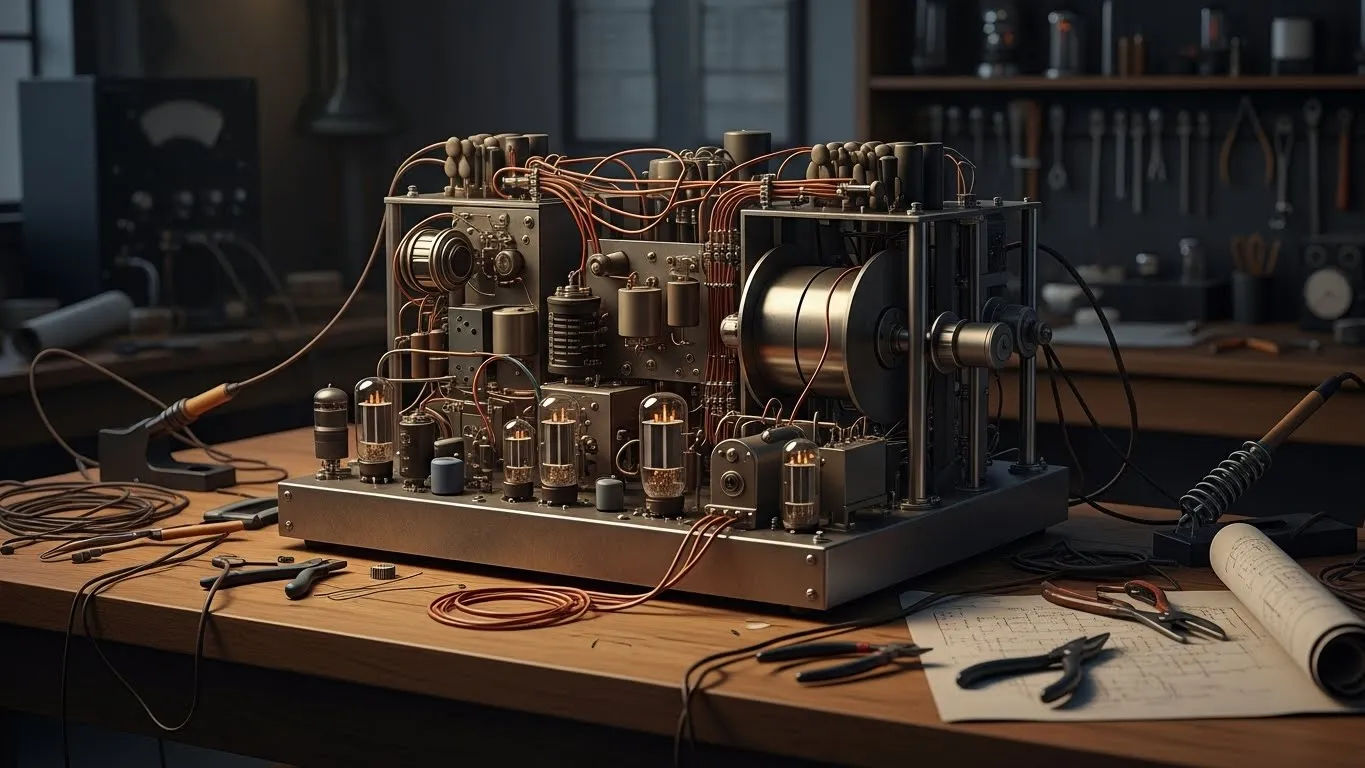

Right then—picture this: it’s 1943. The world’s on fire. Ration books thicker than a Dickens novel. And in a draughty hut on the edge of Bletchley Park, a bloke named Tommy Flowers is bolting together *1,500 radio valves*, miles of wiring, and absolutely *zero* warranty, muttering something about ‘breaking Enigma’. No screen. No keyboard. Not even a reassuring *beep*. Just racks the size of double-decker buses, humming like a hive of very anxious bees. Was this the 1st computer ever? Well—depends who you ask, what you *mean* by ‘computer’, and whether you count ‘thinking machines’ that still needed a cuppa and a cigarette break every 20 minutes. Let’s dig in, shall we? (Spoiler: it’s messier—and more brilliant—than your Year 9 ICT textbook ever let on.)

‘Computer’ Used to Be a Job Title (and It Paid 30 Shillings a Week)

Before silicon, there were *people*—‘computers’, in fact. Mostly women, mostly underpaid, hunched over log tables and slide rules in rooms that smelled of chalk and exhaustion. At the Royal Observatory, at NPL, even at Bletchley, human ‘computers’ crunched ballistics, stellar positions, cipher keys—by hand. One memo from 1941 reads: *“Miss Clarke completed 47 trajectories before lunch. Tea withheld due to backlog.”* Grim. So when we talk about the 1st computer ever, we’re really asking: *when did we stop outsourcing thinking to humans—and start trusting it to boxes that occasionally catch fire?* The shift wasn’t overnight. It was a slow, spark-filled handover… with plenty of burnt fingers.

Colossus: The Secret War Hero That Couldn’t Be Mentioned Until 1975

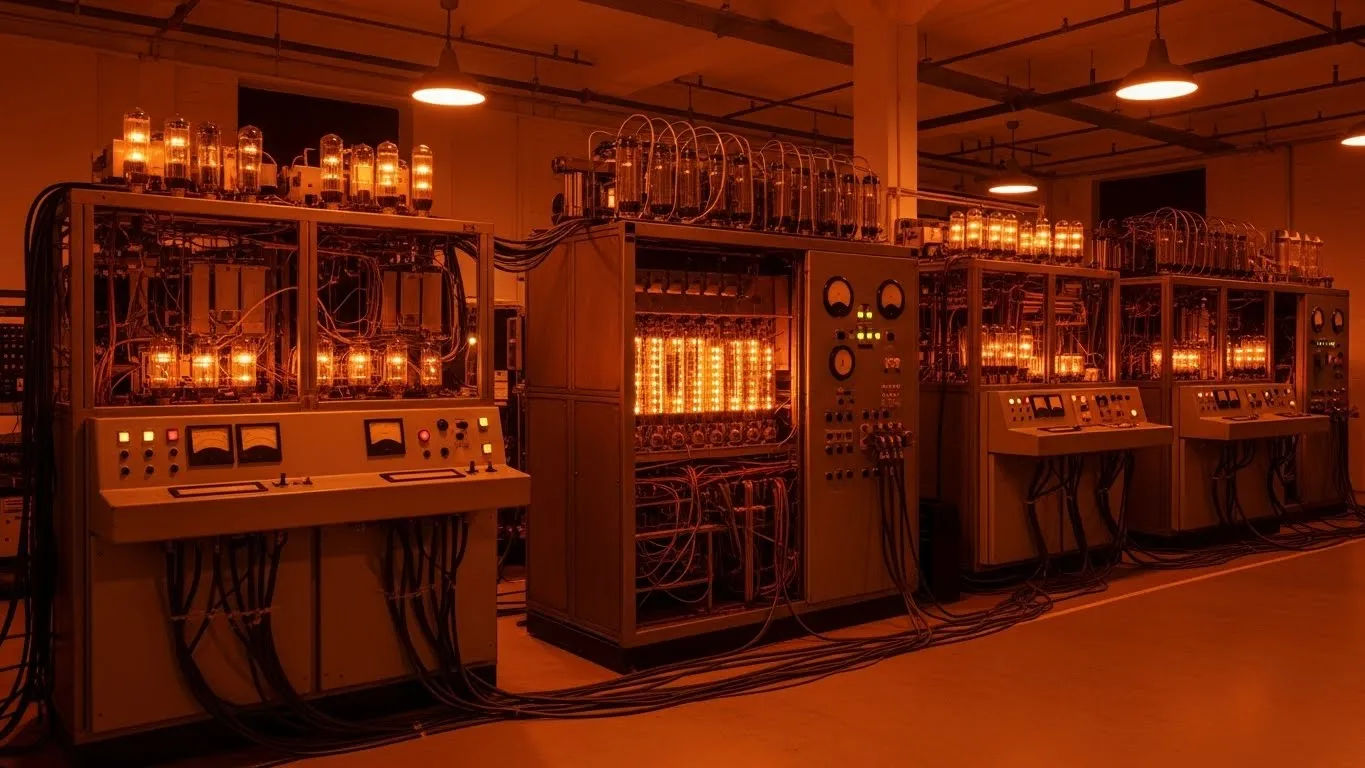

Let’s settle this: the *first programmable, electronic, digital* computer wasn’t American. It wasn’t called ENIAC (though she’s glamorous). It was **Colossus**—built in 1943, deployed in ’44, and *classified* until Margaret Thatcher was already PM. Ten machines, all told. Purpose? Crack German Lorenz cipher—*not* Enigma (that was Bombe’s job; different beast). Colossus read paper tape at 5,000 chars/sec, used Boolean logic, and could be *reprogrammed* via plugboards and switches. Tommy Flowers *insisted* on valves—everyone else said they’d fail. He just… didn’t tell them how many he’d actually used. The 1st computer ever that *mattered*? Arguably, yes. The one that *won the war*? Hard to argue otherwise.

ENIAC: The Glamorous American Cousin Who Got All the Headlines

Enter ENIAC—1945. 30 tons. 17,468 valves. 5 million solder joints. Looked like the control room of a steampunk dreadnought. Publicly unveiled in ’46, it *stole* the ‘first’ crown for decades—thanks to better PR, fewer secrecy laws, and photos of Kay McNulty and Betty Jennings *actually* wiring it (though captions called them ‘models’). Unlike Colossus, ENIAC was *general-purpose*—ballistics, weather, even early nuclear sims. But reprogramming? Took *days*. Rewiring. Literally. One engineer joked: *“We spent more time crawling under it than inside it.”* Still—ENIAC proved electronics *could* compute. And in the Cold War, proof mattered more than precedence. So while Colossus was the quiet genius, ENIAC was the starlet. Both vital to the 1st computer ever story.

Pre-Electronic Contenders: From Babbage’s Dream to Turing’s Blueprint

Nah, let’s not forget the *dreamers*. Charles Babbage’s **Analytical Engine** (1837)—all brass gears, punch cards, and pure vision—was *mechanical*, yes, but *Turing-complete* in theory. Ada Lovelace even wrote an algorithm for it: *“Note G”*, computing Bernoulli numbers. Never built. But in 2002, a team at the Science Museum *did* construct his Difference Engine No. 2—and it *worked*. Then there’s Alan Turing’s 1936 **Universal Machine**—a *thought experiment* that laid the logic for all digital computation. Not physical. Not even *intended* to be. But without it? No Colossus. No ENIAC. The 1st computer ever wasn’t born in a lab—it was conceived in margins, notebooks, and late-night arguments over sherry.

“But What About…?”—Zuse, Atanasoff, and the Transatlantic Patent Wars

Ah, the footnotes. Konrad Zuse’s **Z3** (1941, Berlin)—electromechanical, binary, programmable via tape. Destroyed in a bombing raid. John Atanasoff & Clifford Berry’s **ABC** (1942, Iowa)—first to use *binary* and *capacitor memory*, but not Turing-complete, and never fully operational. ENIAC’s designers *visited* Atanasoff—and later lost a patent case over it. Truth is, the 1st computer ever wasn’t a single ‘Eureka!’ moment. It was a *convergence*—war pressure, theoretical leaps, engineering grit—and a fair bit of transatlantic squabbling over who filed first. Like jazz: invented in a dozen places at once, then argued over in court.

Timeline Tangle: A Rough Guide for the Chronologically Bewildered

Let’s cut through the fog with hard dates (and a pinch of salt):

| Year | Machine | Status | Why It Counts |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1837 | Babbage’s Analytical Engine | Designed, never built | First *concept* of general-purpose programmable computer |

| 1936 | Turing’s Universal Machine | Theoretical | Laid formal logic foundation for computation |

| 1941 | Zuse Z3 | Built, destroyed | First *working* programmable, binary, electromechanical computer |

| 1943–44 | Colossus Mk I/II | Built, used, then dismantled | First *electronic*, *programmable*, *digital* computer—*and* it won battles |

| 1945 | ENIAC | Built, operational | First *general-purpose* electronic digital computer (publicly known) |

Notice the gap between ‘built’ and ‘known’. Secrecy shaped history more than solder. The true 1st computer ever depends on your definition—and whether you value function over fame.

“Did Computers Exist in 1940?”—Spoiler: *Kind Of*, If You’re Generous

1940? Right on the cusp. No electronic digital computers *yet*—Colossus was still sketches, ENIAC a twinkle in Eckert’s eye. But the **Harvard Mark I** (IBM Automatic Sequence Controlled Calculator) was *under construction*—electromechanical, 51 feet long, used for Manhattan Project calcs by ’44. And Turing’s Bombe (1940) *was* cracking Enigma—though it wasn’t a *computer* (more a specialised cipher-breaker). So—did computers exist in 1940? Not really. But the *pieces* were all on the workbench. Like finding a cake recipe… and realising the oven’s still being built.

From Valves to Virality: Why the ‘First’ Still Matters in 2025

You might think: *“Who cares which box blinked first?”* But here’s why it *sticks*: the 1st computer ever wasn’t about speed or storage—it was about *intent*. Colossus wasn’t built to ‘compute’. It was built to *decide*—to choose the right settings, to adapt, to *learn* from data. That shift—from calculator to *reasoner*—is the birth of everything: AI, cloud, your phone knowing you fancy chips at 3 p.m. Even today’s LLMs echo Turing’s 1950 question: *“Can machines think?”* We’re still answering it. Just with better graphics and more emojis.

Where the Past Meets the Present—And Why You Should Care

So—next time your laptop freezes during a Zoom call, spare a thought for Tommy Flowers, rewiring Colossus by torchlight after a valve blew *again*. Or Ada Lovelace, scribbling algorithms a century before the hardware existed. The story of the 1st computer ever isn’t just tech history—it’s *human* history: stubborn, collaborative, occasionally explosive. Fancy diving deeper? Pop over to The Great War Archive for more on innovation under pressure. Love timelines and tech? Our History section’s packed with gems. And for a proper nostalgia trip? Don’t miss 70s Computers: Tech Revolution—where beige boxes ruled, and 64KB *felt* like infinity.

Frequently Asked Questions

What was the first computer ever found?

The title of ‘first computer ever’ is contested, but **Colossus (1943–44)** holds strong claim as the first *electronic, programmable, digital* computer—built at Bletchley Park to break German codes. Though kept secret until 1975, its existence rewrites the narrative of the 1st computer ever, proving Britain led the electronic computing race—even if America got the headlines.

Did computers exist in 1994?

By 1994? Blimey, yes—computers were *everywhere*. Windows 3.1 dominated, the World Wide Web was going mainstream (Netscape launched that year), and the average UK home with a PC likely had a 486DX running at 66MHz. Compared to the 1st computer ever, 1994 was practically sci-fi: CD-ROMs, dial-up, and Doom LAN parties. Progress moves fast when you start with valves and end with Pentiums.

Did they have computers in 1972?

Absolutely—1972 was a golden year. Intel launched the 8008 microprocessor, Xerox PARC built the first GUI workstation (the Alto), and the first *personal* computers were emerging (like the Micral N). Universities, banks, and governments ran mainframes—IBM System/370s humming away in air-conditioned basements. Lightyears from the 1st computer ever, but the bridge from Colossus to Commodore was well under construction.

Did computers exist in 1940?

In 1940? *Almost*. No fully electronic digital computers yet—but the pieces were assembling. Turing’s Bombe (mechanical, cipher-specific) was operational at Bletchley. Konrad Zuse was finalising the Z3 in Berlin. Harvard and IBM were building the Mark I. So while the 1st computer ever hadn’t *quite* blinked to life, the world was holding its breath—and reaching for the soldering iron.

References

- https://www.turingarchive.org/

- https://www.bletchleypark.org.uk/colossus

- https://www.computerhistory.org/revolution/birth-of-the-computer/4/1

- https://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/objects-and-stories/computing/babbage-engine